If you’re reading this, my guess is you don’t need a primer on why you should be improving conversions – as opposed to just getting more traffic, or just developing products– in your sales funnel.

You’ve already paid to acquire your website visitors. Why not sell to more of them? That’s the short definition of conversion optimization.

And a large number of businesses get it…

According to Unbounce, 44% of businesses were using split testing software as of 2013.

Sumome’s homepage boasts 454,482 websites-and-counting using their tools to improve opt-in conversions.

Fearing missing out on this opportunity, you might be tempted to hire an optimization team, and just throw money at them.

“Do something! Anything!”

But, as I’ll demonstrate below, budgets are finite, and there’s a cost to focusing on optimizing the wrongthings.

So how are you supposed to know where to start?

Should you compare your results to industry-specific benchmarks, or should you just pick a conversion rate that looks “low” and start trying to optimize it?

I’m going to argue that both of those approaches are wrong. For starters…

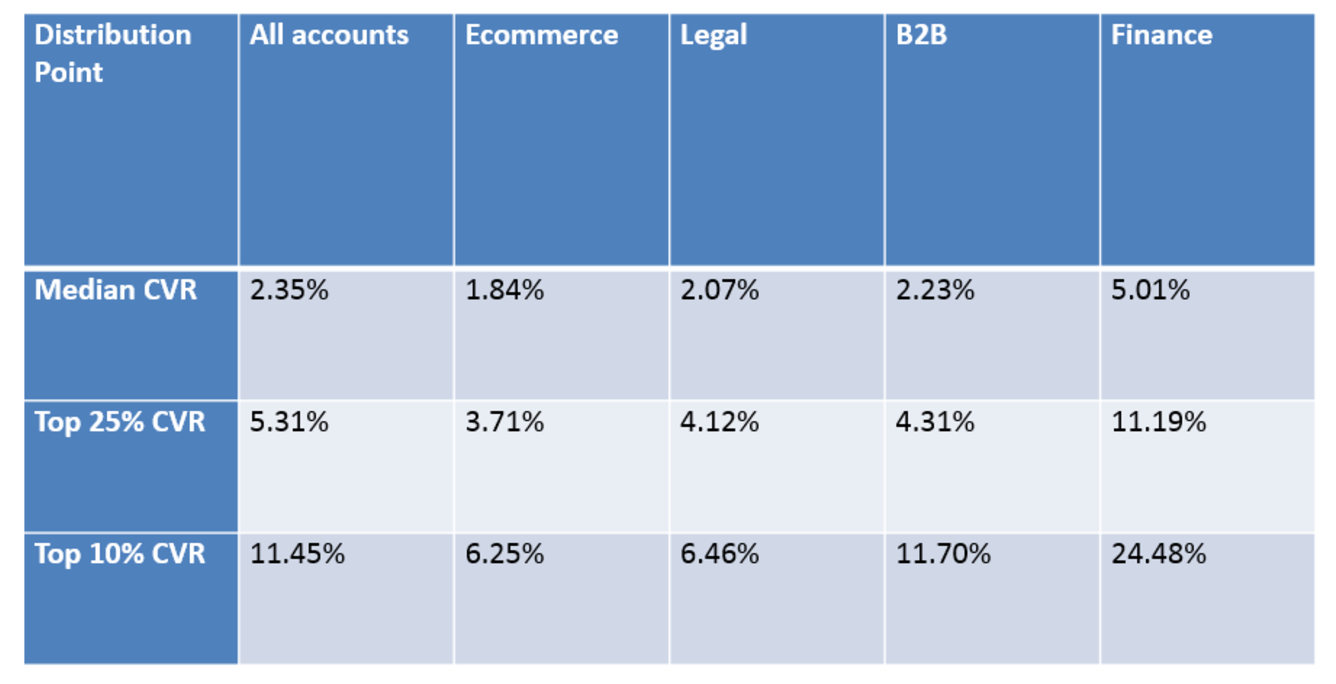

A lot of industry-specific conversion rates are hard-to-interpret

You may have seen statistics like these…

Metrics like the above are next-to-useless unless you know what part of the funnel you’re measuring.

To begin with, what counts as a “conversion”?

Is that sales relative to site visitors? Is that orders relative to people who request a quote? Those are two conversion rates with benchmarks that differ by at least an order-of-magnitude.

Besides, “B2B” as a vertical?

We’re pretending that, say, lead gen for architecture firms is so similar to enterprise scheduling software for Boeing that a single, apparently fine-grained, benchmark can circumscribe both? And would selling a SAAS product to law firms count as B2B, or “legal”?

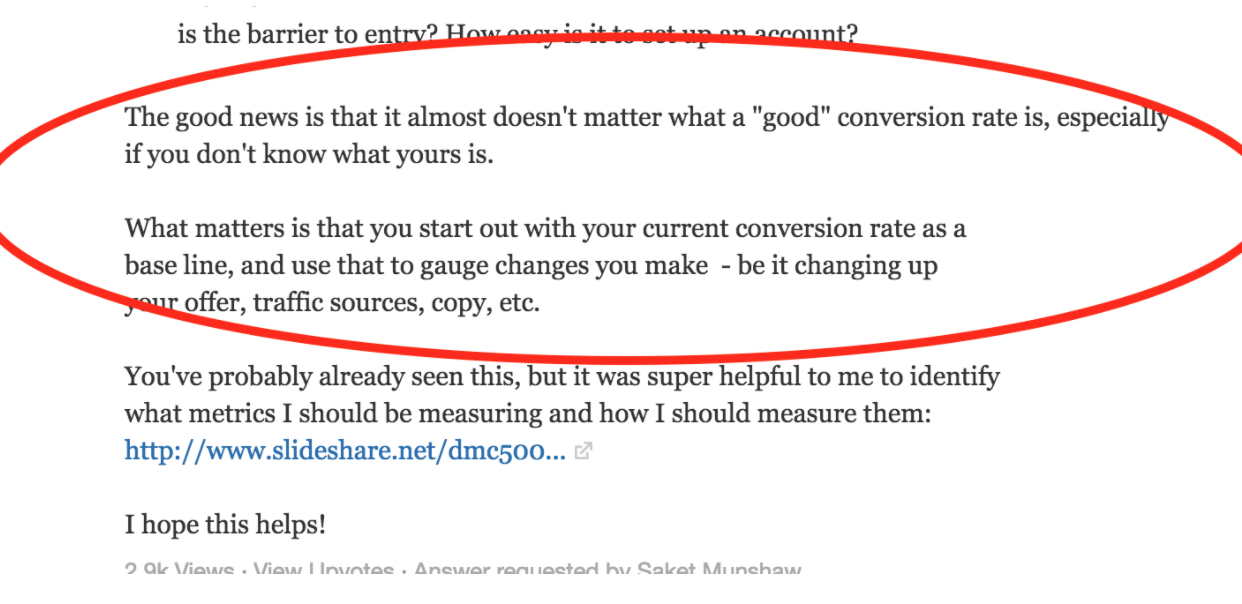

On the other-hand, you can’t simply “pick one and go with it”

Here’s a familiar, and equally annoying, canard from the other sideof the argument…

It “doesn’t matter” what a good conversion rate is?

Just “pick one and improve it”?

There are two big reasons that’s a bad idea: diminishing marginal returns and opportunity cost.

Diminishing returns means sometimes one unit of effort will produce one unit of reward, like accelerating a car from zero-to-30, when there’s low air resistance. But in other contexts one unit of effort will produce far fewer returns, like trying to accelerate a car from 100-130, when every extra ounce of speed requires way more energy than going from zero-to-30, because of friction and wind-resistance.

It’s the same thing in your funnel.If you’ve got a 1% opt-in rate from the front page, I don’t care what industry you’re in: there’s an opportunity for a big win for just a little time spent on your design and copywriting.

If, however, you’re converting at 25% for sales from a webinar, I can promise you that every extra percentage point is going to require a lot of time and effort.

Opportunity cost means that in the real world, you can’t pursue all strategies at once: time and money are limited. That means every hour you pay your team to work on one problem is an hour they can’t be working on something else.

What if spending time and money improving one metric causes you to ignore another one that could be a bigger win?

Bottom line: You need something to tell you whether small efforts optimizing a particular part of your funnel are likely to yield large rewards, or if it’s the other way around.

To accomplish this, let’s borrow a page from Sir Thomas Bayes, for whom Bayes’ Rule/Theorem is named. If you want specifics, just google it, but for the purposes of this post, Bayes gave us a way to start with an educated guess about a rate or probability, then refine as you start to get data from the real world.

For example, I know from Ramit Sethi that a good universal benchmark to aim for in terms of sales relative to total people who see an offer is 1-2%.

Knowing that number will save you a lot of trouble if your list-to-sale rate is already 3%. (More below on what to do in that scenario.) But my own experience in my own business and with clients has revealed that rate to be a bit low.

No problem, Bayes would tell us: you can start with these numbers, then adjust as you get more real-world data.

What follows are good “educated guesses” about where to start, with the obvious caveat that you’ll refine them for your specific business as data comes in:

Conversion Rate Benchmarks: Opt-Ins vs. Sales

Are you asking for email addresses, or money?

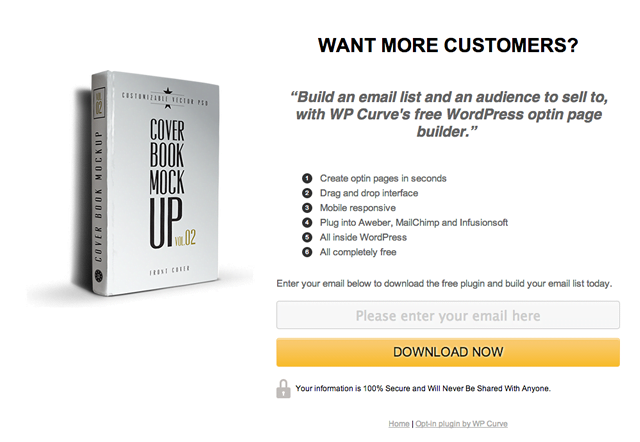

If it’s the former, and you’re converting at less than 10%, you probably have a problem.

Here are a few examples:

- Homepage: get my free guide, in exchange for your email address

- “Content upgrade”: get the exact tool I used to accomplish this thing I’m telling you about, in exchange for your email address

- Landing page: join my free live video training to solve xyz problem. Just enter your email address to sign up

A typical email opt-in landing page

In the case of the latter, however – when you’re offering something that isn’t free – Ramit Sethi will tell you if you’re converting between 1 and 2%, you’re good to go.

Examples of instances where that conversion rate benchmark would apply:

- Number of people who buy, relative to number of people in an email list segment who get an email about a product launch.

- Percentage of people who sign up for a webinar (not attendees) who buy, especially with high-priced services like consulting. (This includes instances where a sales call is an intervening step.)

Caveats are many:

In real life, I’ve seen both good sales sequences/pages and webinars convert much better. I’ve also seen super dialed-in copy fail to convert, especially with paid traffic.

But you can do as Thomas Bayes would: start with the benchmark, then adjust-as-needed as you get more data.

Here are a few likely time-wasters those benchmarks will already help you avoid:

- Optimizing the snot out of a landing page that’s already getting 15% opt-ins.

- Rewriting a sales page that’s already converting at 3% relative to the list segment, if your opt-in rate is only 3%.

Outliers like “Request a Quote”

Not all businesses will have an email opt-in front-and-center on their homepages. Some will invite customers to “view pricing”, or “request a quote”. (These CTAs are extremely popular with web agencies, for some reason.)

A typical “get a quote” landing page

How are we supposed to evaluate a conversion rate on a “request a quote” CTA? The Dumb Way. Here’s what I mean…

We know the benchmark for opt-ins…

…and we know the benchmark for sales…

Since the commitment level of requesting a quote is somewhere “in between” that of getting a free lead magnet/signing up for a webinar, and that of actually pulling out your credit cardand buying, a good place to start is “in between”.

If fewer than 1% of visitors are requesting a quote, you’ve got a problem.

If more than 10% are, I need to copy your landing page immediately.

If it’s somewhere in-between, we need to ask a more nuanced question…

What’s this customer costing me to acquire, and is it less than he would cost by simply collecting an email address, then selling to the list?

Here’s what I see most-often in real life: “request a quote” CTAs that either aren’t converting well, are one of multiple, conflicting CTAs (hedging their bets by including both a quote CTA and a lead magnet), or both.

Does your page have too many CTAs?

There’s a smart, and a dumb way to test this:

(And to reiterate, for purposes of this post, Dumb doesn’t mean Bad – it just means “so obvious smart people might overlook it”.)

Smart: split-test two pages, and tag people who opt-into the list first differently than those who buy directly after requesting a quote, then count the number of sales tagged with each.

Dumb: send a survey, asking buyers “did you buy directly off my homepage, or did you subscribe to my list first?”

If the majority of buyers are coming from the list, and/or your “request a quote” rate is low, consider losing it altogetherand just collecting the email. You can always use an upsell page that invites people to request a quote immediately after the opt-in.

Even if a big percentage are requesting a quote directly, why not do both?

- Make the first question of the questionnaire “so I know where to send this customized assessment, please enter your best email address”, and make a click to the next page submit the email address.

- Consider using a tasteful exit pop-up(this is one of the few instances in which I recommend this, as I feel people rely far too heavilyon the exit pop-up, and it’s trashing many of their brands). If most potential buyers request a quote, there’s nothing to lose offering a lower-commitment offer to those who don’t – you can always sell to them later from the list.

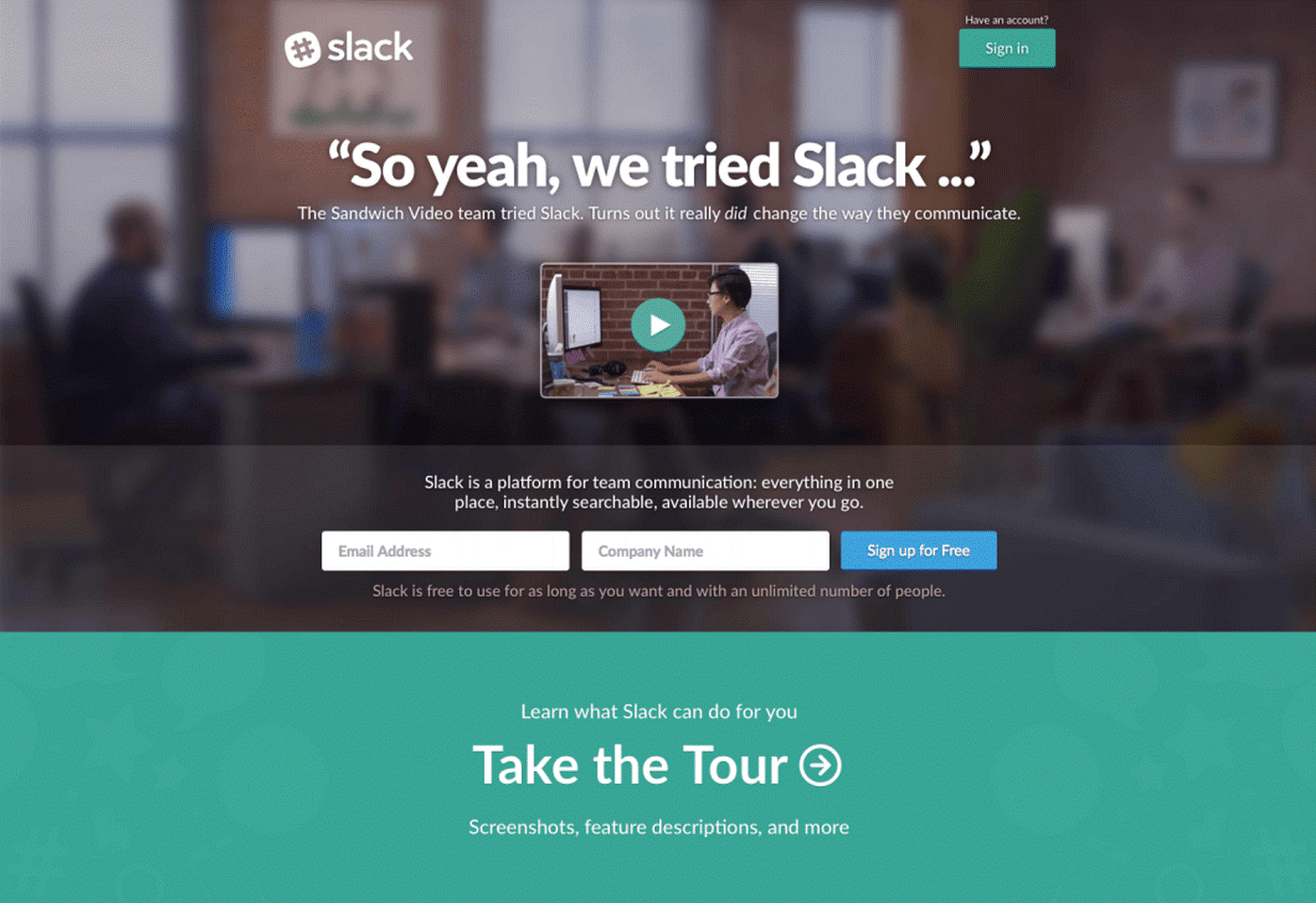

Slack’s awesome landing pages give the visitor only one action to take above the fold

Here are a few time-wasters having the above framework in mind will save you from:

- Sinking months into split-testing “request a quote” offers that aren’t even driving the majority of sales, while you’re losing the opportunity to collect thousands of email addresses from potential buyers.

- Wasting resources trying to optimize a “request a quote” CTA that’s already converting well (say, at 7 or 8%), instead of calling it “good enough” and moving on.

How to Do It in Real Life

Here’s a thought experiment I like to use in my talks: your business owes money to the mob, and you’ve got only 30 days to double your profits. And this has to be paid in installments, not lump sum. (Nice try, ace. I see what you’re doing…;)

So you’ve got to double your MRR, or monthly recurring revenue. That rules out a one-off fire-sale/launch, or a Hail Mary joint venture.

Luckily conversion optimization can produce 1.5x-or-bigger wins in just the time it takes to copywrite a page and split test it. String together a few wins at that scale, and your biggest problem might be concealing all that extra money from the mob.

In such a scenario, here’s a decision tree you might follow…

What’s my list-to-sale rate?

Know what to check in your funnel

As above, that just means “how many people who see a link to an offer are buying?”

Most generally, this asks “once people opt-in, is my funnel doing its job?”

Less than 1%? You could probably benefit from some copywriting and positioning help on sales pages and webinars, and within email sequences. (This assumes you have product-market fit, a topic for another day…)

Action: write it down. How much less than 2% is it? How big a win would bringing it up to 2% be?

Greater than 2%? Not your biggest win.

Action: move on.

What’s my opt-in rate?

As above, this is number of people who join your list relative to unique visitors to your site.

Less than 10%? You could probably benefit from some copywriting and design on your homepage, landing pages, and most popular content pieces. (For starters, if you’re not using one of Sumome’s tools, you should be.)

Action: Write it down. How big a marginal win would coaxing this rate above 10% be?

Greater than 10%? Probably not your biggest win.

Action: move on.

What if both rates are above benchmarks?

3 possibilities:

- You’re super dialed-in, and you need to raise prices. If list-to-sale is greater than 4 or 5% (or more than 20% from a webinar, relative to attendees), consider raising your prices. If rates drop below benchmarks, then you can use copywriting and design to bring the rates up, but you’ll know you’re throwing your resources at the right rates.

- You’re super dialed-in, and you need traffic. Hey – sometimes traffic is the biggest win.

- You’re over segmenting, or adding needless apertures to your funnel, so that you’re reducing needlessly the number of people who ever see an offer.

If it’s #3, ask yourself the following: “how many ‘segmentation points’ (places where customers have to take an action to proceed to the next phase) am I making people go through before they see an offer? Could I reduce that number?”

How many bottlenecks are you requiring your customers to pass through?

(For more detail, read this post)

And there you have it. I’ve demonstrated the folly of both overly-specific-seeming benchmarks, and of no benchmarks-at-all, for improving sales through better conversion.

The solution? Not “smarter” benchmarks, but Dumber ones. And a smarter strategy to learn from them.

About the author

Nate Smith is a direct response copywriter and sales funnel strategist who helps businesses double their earnings with their existing traffic.

0 Comments