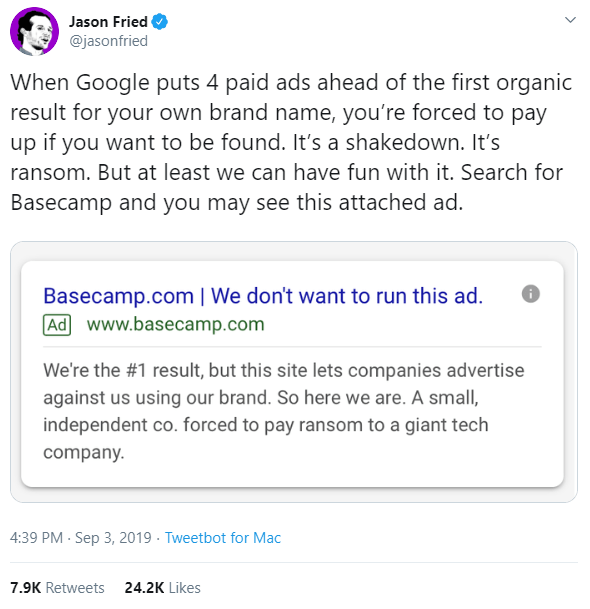

Yesterday, Basecamp co-founder and CEO Jason Fried took to Twitter to criticize Google for allowing advertisers to bid on their competitors’ brand names:

Via Twitter user @jasonfried.

Here’s the crux of Fried’s argument: By allowing advertisers to bid on their competitors’ brand names, Google forces businesses like Basecamp—which sells a popular project management tool—to pay for traffic that they would have otherwise gotten for free via the organic results.

(Free in the sense that you don’t pay for organic clicks. SEO does, of course, cost money.)

As you can see, Fried’s tweet has gone viral—amassing tens of thousands of retweets and likes in only 24 hours. Head over to his Twitter profile and you’ll see that he’s kept the conversation going into today, mostly with people who share his frustration.

Let’s consider both sides of the debate Fried has sparked.

Fried makes an important point …

Google makes an insane amount of money on ad clicks—billions of dollars each year on search ads alone. It’s a business model that’s helped make Alphabet, which owns Google, one of the most profitable Fortune 500 companies in the US.

Would that change if Google stopped selling ad space on businesses’ brand names? Absolutely not. We don’t know how much revenue Google makes on competitive search ads specifically, but we can assume it’s (relatively) small enough that its disappearance wouldn’t spiral them into the red. Google can afford to stop letting advertisers bid on each other’s brand names.

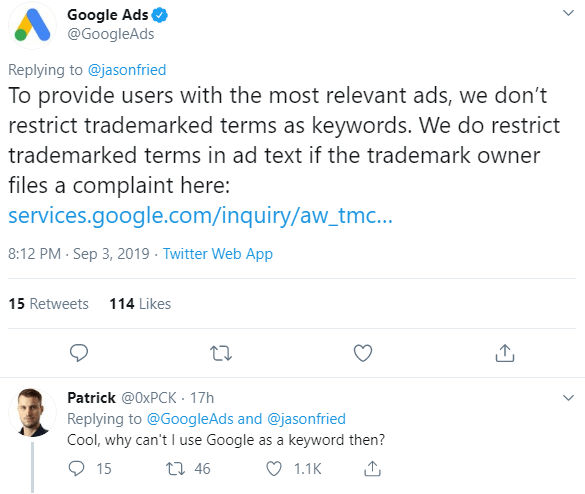

(By the way, you can’t bid on Google’s brand name or use it in your ad copy. Just sayin’.)

Well done, Patrick.

As Fried points out, banning competitive ads would help businesses smaller than his save some much-needed dough. If the search query “basecamp”—monthly search volume of over 240,000, for those who were wondering—only generated organic results, the company could drive valuable, high-intent traffic to their website without having to pay for clicks.

Google (and Alphabet) remain immensely profitable. Businesses sweat a little bit less about their marketing budgets. Sounds good to us.

… but there are valid counterarguments

Full disclosure: I recently wrote a blog post about the best competitive ads we’ve seen in the Google search results.

As I discuss in that post, there’s more than one reason as to why someone may search for a brand name on Google. On the one hand, the user’s intent could be navigational—meaning they’re simply trying to get to the website of whatever company they’re looking for. If this is the case, Fried’s argument is spot-on: Because the user is deliberately looking for one company in particular, that company shouldn’t have to pay for the click.

On the other hand, the user’s intent could be informational—meaning they’ve heard of the brand they’re searching for and they’re using that name as a starting point to learn more about the product or service they sell. If this is the case, competitive ads are fair game. If a sleep-deprived yuppie hears a podcast ad for Casper and excitedly searches their brand name on Google, is it so wrong that Tuft & Needle serves him this ad?

Because his intent is purely informational and he’s not looking to make a purchase right this second, it’s not exactly a crime to let him know about an alternative option.

To get a second perspective, I asked our in-house SEO specialist, Gordon Donnelly, for his thoughts on the matter:

“The organic Google search results generate a ton of revenue for businesses like Basecamp—on branded terms and otherwise. Having to buy ads to appear at the very top of the SERP is simply the price you have to pay to be in the game.”

When I pointed out to Gordon that some of those branded terms are navigational in intent, he made a damn good point:

“Basecamp still has the advantage. They’re worth $100 billion, whereas a competitor like Monday is only worth $2 billion. Having to bid on their own brand name isn’t exactly cutting into their profit margins.”

That’s especially true when you consider the relatively low cost of bidding on your own brand name—a trend we see due to the nature of Google Ads’ quality score metric. More importantly, Gordon’s broader point is that running competitive ads is an important tactic for companies trying to carve out market shares in crowded industries. If your chief competitor generates a ton of monthly Google search queries, it follows that you’d try to get in on a little bit of the action.

Although Basecamp is small compared to Google, it dwarfs some of the other companies in its space—Monday included. What choice do those other companies have but to advertise?

The bottom line

There’s no point in debating why Google allows search advertisers to bid on their competitors’ brand names: It’s simply another way for the company to make money. Considering how much money Google would make even if they didn’t allow competitive ads—and considering the fact that Google has made their own brand name off-limits—we understand Fried’s frustration.

That being said, competitor targeting (a.k.a. paid search conquesting) isn’t an inherently bad tactic—even if does feel a bit … wrong. In some cases, it allows advertisers in competitive industries to gain some additional exposure for their brands.

It’s not black-and-white, but for now, it’s the way it is. We’d love to hear your thoughts in the comment section below!

0 Comments