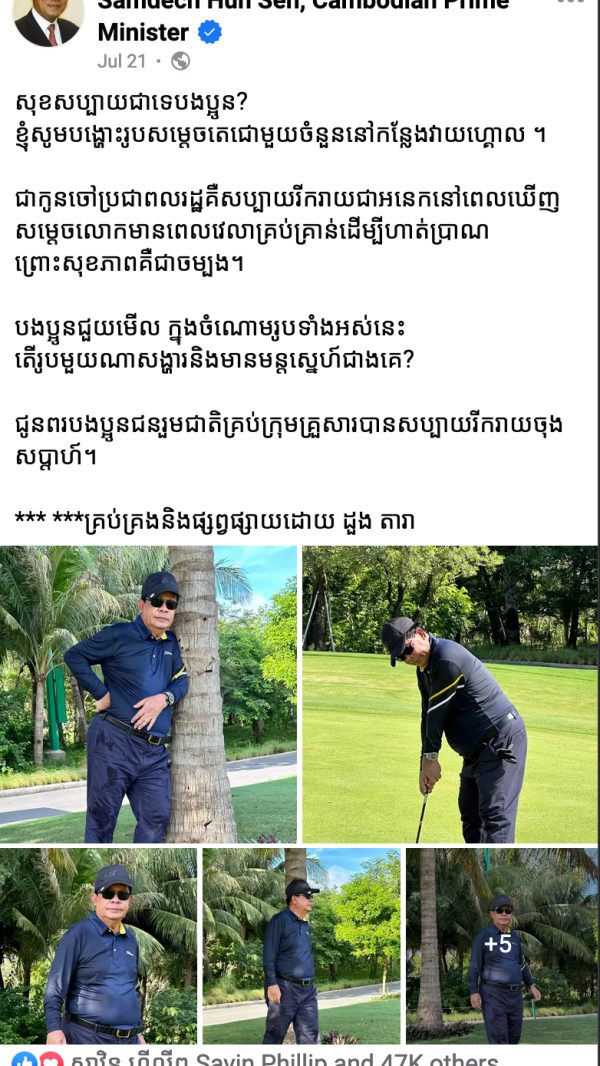

Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen is back on Facebook. One month after dramatically quitting the platform and nearly banning it from the country entirely, his 14 million followers can find dozens of fresh posts on his page — sharing news updates, patriotic music videos, and even posed photos from a day on the golf course. The posts are now signed off as “managed and promoted” by his adviser Duong Dara, hinting that the leader hasn’t fully forgiven his favorite social network.

It’s the result of a strange stalemate between one of the internet’s largest platforms and one of the longest-serving heads of state in the world. At the end of June, the independent Oversight Board found that a speech made by Hun Sen qualified as inciting violence and recommended that Meta suspend him from their platforms for a minimum of six months. Sen responded by preemptively quitting — but the weeks since have shown a surprising indifference from Meta over the prime minister’s ongoing presence on Facebook.

In a statement after the ruling, Meta committed only to banning video of the speech, saying the company would “conduct a review of all the recommendations provided by the board in addition to its decision, and respond to the board’s recommendation on suspending Prime Minister Hun Sen’s accounts as soon as we have undertaken that analysis.” According to the bylaws of the Oversight Board, Meta has 60 days to respond, giving the company until August 28 — but the result has left Cambodia in an uncomfortable limbo.

In the meantime, Hun Sen has been free to use Facebook to amplify threats and other content in the days leading up to the election. He faced no meaningful opposition in the election, having disqualified the main opposition party on a technicality. But he tested Meta’s limits by reposting the same violence-inciting video that was banned by the Oversight Board. Hun Sen’s post has since been taken down, but the account has not suffered any visible repercussions for reposting it. Meta did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the matter, simply referring reporters back to the previous statement.

Hun Sen has pledged to step down as prime minister next month, allowing his son Hun Manet to take the position, but he’ll remain a powerful figure even without the official title office. Outside of Facebook, Hun Sen’s control over the Cambodian state is unchallenged. On July 4, the Cambodian government ratified an amendment to the voting law based on one of Hun Sen’s orders: the law commands that any aspiring political candidates vote in the current elections in order to qualify in the future, while also criminalizing any person who encourages voters not to go vote. Though it’s not explicitly in the text of the law, Cambodia’s election authority added that it considers a campaign to destroy or improperly mark ballots a criminal offense as well. That control extends to activity on Facebook, where anyone critical of the regime is quickly bombarded by trolls and brigade reporting.

Gayatri Khandhadai, the head of tech and rights for the Business & Human Rights Resource Center, said that the Oversight Board case demonstrates how Meta and other tech platforms are failing to uphold their values in Cambodia.

“In a critical democratic moment, it’s really important that authorities enforce rights and guarantees and protections because the environment is charged,” she told Rest of World. “It’s easy to excite people, and there are consequences.”

The recent troubles began with an alarming speech made by Hun Sen on January 9, warning opposition groups that he would use “legal means” or a “stick” to prevent them from taking over the government. The speech was quickly followed by offline violence and threats against opposition groups, driving home the leader’s implicit threat. Video of the speech was reported three times as a violation of Facebook’s rules against inciting violence, but the platform waffled over whether video of the speech should be banned. When the issue finally reached the Oversight Board, the ruling was unequivocal: Hun Sen’s speech was incitement to violence, and the company shouldn’t have let it spread on Facebook.

“Given Hun Sen’s reach on social media, allowing this kind of expression on Facebook enables his threats to spread more broadly,” the board concluded. “It also results in Meta’s platforms contributing to these harms by amplifying the threats and resulting intimidation.”

Hun Sen did not take the decision with grace, first deleting his page and then suggesting he might block Facebook’s access in the country, as other authoritarian governments have attempted. In the end, he opted not to cut off Cambodians’ access to Facebook but pledged that the government would cut all ties with the network.

“Allowing this kind of expression on Facebook enables his threats to spread more broadly.”

But even before his official return, Hun Sen’s face and party were all over Cambodian timelines — in part because of paid promotion. Facebook records show that Hun Sen’s son Hun Manet has placed 71 ads since July 3 alone. The page for the Cambodian People’s Party — over which Hun Sen currently presides — has posted 65 advertisements on Facebook since July 1, all of which cost between $1 and $100, according to Meta’s Ad Library.

Hun Sen also has allies outside politics who have gone to bat for him on Facebook. Leng Navatra, a prominent Cambodian businessman with close ties to the prime minister, posted 28 ads since the June 29 decision. None of his ads were for promoting his businesses, instead focusing on politics. Almost all of them include videos of different groups of Cambodian citizens with the caption, “Cambodians call on all voters to go to the polls on July 23.” This is likely a reference to the newly ratified voting law requiring Cambodian citizens to vote in the upcoming election if they want a chance to run as a candidate in future polls.

Navatra even posted an ad featuring a video of himself speaking in revolt of Meta’s decision against Hun Sen’s speech, captioned in Khmer, “No matter how big the company, if it violates our sovereignty, we have the right to leave together if necessary.” He spent between $2,500 and $3,000 on that ad, earning more than 1 million impressions, according to the Meta Ad Library. Navatra didn’t respond to a call nor a Facebook message to his account.

That money — and the inescapable Facebook presence it buys — have a profound effect on everyday Cambodians. In 2015, Facebook introduced Cambodia to its Free Basics program, an app that provides access to basic internet services through Facebook. The platform has since become almost synonymous with the internet, especially in the rural countryside. As a result, Facebook is also the primary platform for advertising a business or political campaign.

14 million The number of followers Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen has on Facebook.

Trolls friendly to the regime have continued to operate unimpeded, even as Hun Sen himself has drifted on and off the platform. Uy Rithy is a content creator who spoofs the popular Chinese drama Three Kingdoms and sometimes reiterates the prime minister’s talking points via his impersonations of a warlord called Cao Cao. In between sharing the videos he creates, Rithy has also been promoting his work as a member of the ruling party’s youth division on his Facebook page. While Hun Sen has kept Facebook at arms’ length, he’s actively promoted Rithy’s content through other means, playing one of Rithy’s videos to an audience of garment workers who listened to his speech on June 24 and then hiring the content creator as an advisor on July 3.

In a Facebook message, Rithy insisted that his page was not political, adding that “maybe you don’t know or follow my page, so you’re not a fan.”

Meanwhile, anyone viewed as an enemy by the regime quickly finds the platform almost unusable. Men Nath, a Cambodian political analyst living in Norway, said that his page has been targeted by anonymous government supporters since 2022, leading to his losing abilities and reach on the platform. Though he doesn’t speak directly about politics, he said he speaks regularly about a sensitive topic in Cambodia: border issues.

Earlier this year, he went on a talk show on one of The Cambodia Daily’s Facebook pages and then found himself barraged with comments from anonymous users.

“I had to delete a lot of my previous contents on Facebook page to restore my page with almost 50,000 followers,” Nath says. “Nowadays my Facebook page cannot post anything.”

0 Comments